Back when I was in high school – in the last 70’s and 80’s – there were four ways to listen to music.

You could listen to the radio. There was music on AM radio, but if you cared about music, you listened to FM radio. In my case, it was album-oriented rock radio.

Or, you could listen to your records. This gave you great sound, but 1) records degraded slightly each time you played them, 2) to get the best sound, you needed to follow an elaborate cleaning ritual, and 3) if you liked your music loud, the record would skip. Oh, and 4) they weren’t very practical for your car.

For your car, you could obviously listen to the radio, you could listen to 8-track tapes, a weird and clunky format that wasn’t very good.

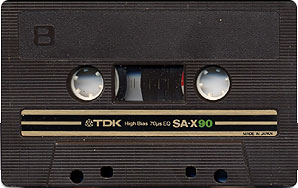

Or, you could listen to a compact cassette – what everybody just called a cassette. Cassettes were small, easy to carry, and had decent sound. The record companies sold a ton of pre-recorded cassettes, which had a limited lifetime, sub-par sound (because they were duplicated at high speed and used cheap speed), and – if you were unlucky – would transform itself into a large wad of crumped-up tape. Interestingly, pre-recorded cassettes generally cost more than record albums.

If you wanted the best sound – and if you wanted to be cool – you had a stereo of your own, you bought albums, and you recorded them onto blank tape that you bought for $3 or so. And – if you bought 90-minute tapes – you could fit two albums on a single tape.

Okay, so, that wasn’t quite accurate. You bought *some* albums, but most of your music came from recording albums that friends. Because this was a bit of a hassle to do, you wanted to use a tape that was good quality. Most people I knew chose a specific brand – and often a specific tape – and stuck with it. At one point – around 1982 or so – they came out with a 100-minute variant, which was great because you could use it for albums that were longer than 45 minutes in length.

In my case it was the TDK SA-X90 pictured above, in a number of variants over the years. In college, I had a tape holder on the side of my stereo cabinet that held 48 individual tapes.

And then CDs came, then MP3s came, and then portable music players came, and cassette tapes went away. Though I found it difficult when I finally decided to get ride of them.

If *any* if that has any resonance with you, you might want to spend a few minutes on Project C-90.